I’m back with good news and bad news. Good news: my Substack migration seems to have worked! Bad news: I bring you another article about the ballot question for this election. But the slight wrong-ness of this conversation has bugged me for the past month, and I need to get it out.

I’m also going to try to record audio versions of my newsletters for my multitaskers. Bear with me, I’m sure it’ll take some time until they’re any good. :)

In case you’re unfamiliar, a ballot question is essentially the central choice of a campaign. It’s meant to represent what’s on voters' minds as they mark their ballot. It’s not a simple “Do I like candidate a or candidate b,” but more so “With this vote, I’m supporting x direction instead of y.” Sometimes parties compete on the same ballot question, and other times they try to stake out different terrains.

There have been many discussions of what the ballot question was and for which groups, but few reflect precisely what I heard from voters throughout the campaign and what I’ve seen in my own data.

It wasn’t just Trump. It was Canadian identity.

I’ve seen a few definitions of the ballot question for this campaign, most of which come down to:

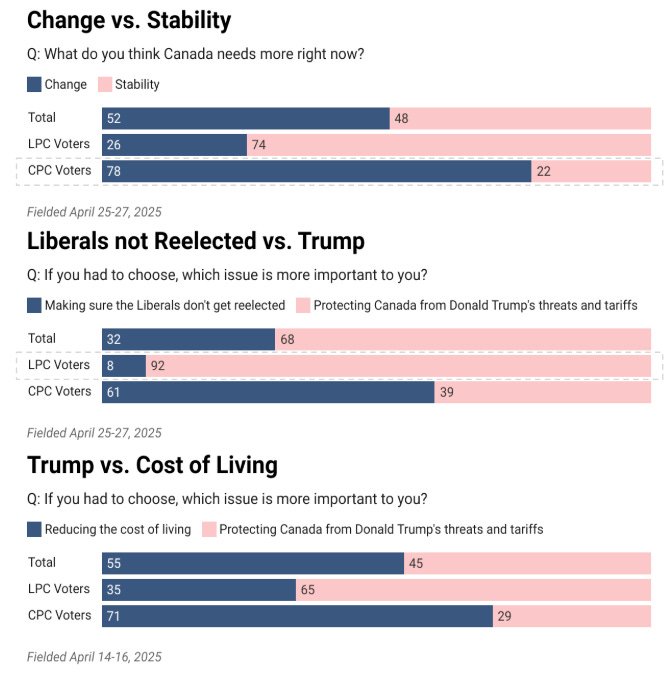

Change vs. stability

Trump vs. the cost of living

Trump vs. change

I’ve also seen some (Brad Wall) define the campaign as an emotional duality: hope vs. fear. With all due respect to the high lord of my homeland, no. Debunking global statements about the public’s emotional state is one of my passion projects, and will be part of my next newsletter.

I agree with most analysts that this election was all about change for Conservative voters. In a forced choice between change and stability, 78% of Conservative voters chose the former. They’re holding on tightly to their Trudeau disdain (80% have an unfavourable view of him) and want a change in policy direction on a wide range of issues, primarily economic.

Trump was certainly a huge factor for Liberal voters. Nearly all Liberal voters thought protecting Canada from Trump’s threats and tariffs was more important than a change in government. At mid-campaign, 2 in 3 LPC voters prioritized protecting Canada from Trump over reducing the cost of living.

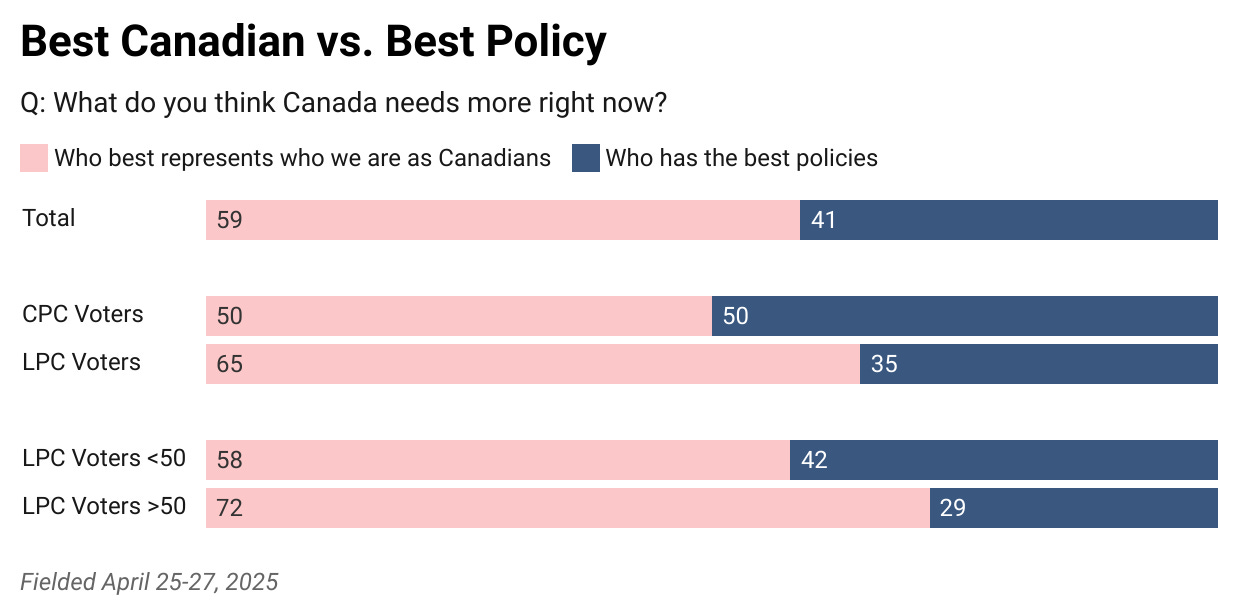

But some of this depends on how you ask it. I tested an additional ballot question: Do you think this election is more about choosing who best represents who we are as Canadians or who has the best policies? 59% of Canadians said the election is more about choosing the best Canadian. This is higher among Liberal voters, driven by Liberals older than 50, nearly 3 in 4 of whom thought it was about choosing the person who best represents us as Canadians.

To older Liberals, yes, Trump’s tariffs were a huge factor in the election, but that was just the beginning of their reflection. 83% of LPC voters >50 agreed, “recent events, including the election and Trump’s threats, have made me reflect on what it means to be Canadian”. This compares to 70% of LPC voters <50, and 58% of Conservative voters. These elder Liberals looked at Donald Trump and MAGA Republicans as a flashing warning sign. They feared the damage that Trump could cause to our economy, were disgusted by Trump’s “51st state” comments, and were also scared of Trump-style politics infiltrating Canada. To them, this election was about preserving our Canadian identity.

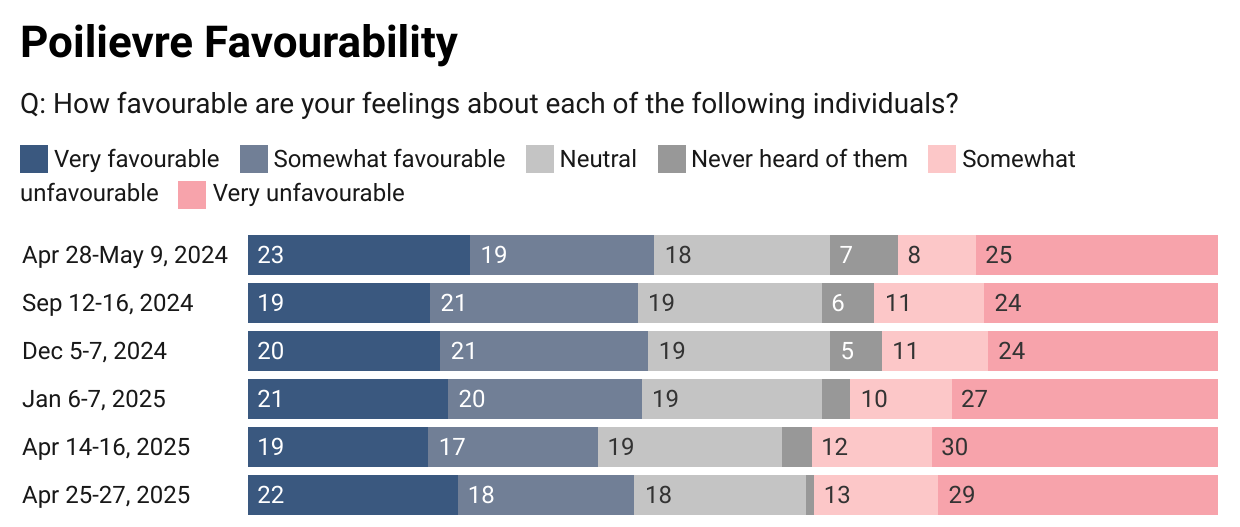

Enter: Pierre Poilievre. Poilievre has always been polarizing, and while his unfavourables have worsened over the past year (+9 total unfavourable, +4 very unfavourable), it didn’t change as much as the public discourse suggested. Rather, Trump’s attention on Canada made Poilievre’s demeanour matter. He changed many Canadians’ standards for leadership.

I think of support for the Liberals in this election as a 3-legged stool. It was based on 1) liking Mark Carney, 2) recognizing the American threat, and 3) disliking Poilievre. There was certainly interplay between these factors (ex., voters liked Carney because they believed he’d be good at handling the American threat), but all 3 elements were important to solidifying the core Liberal vote and pulling in both lapsed and strategic Liberal voters.

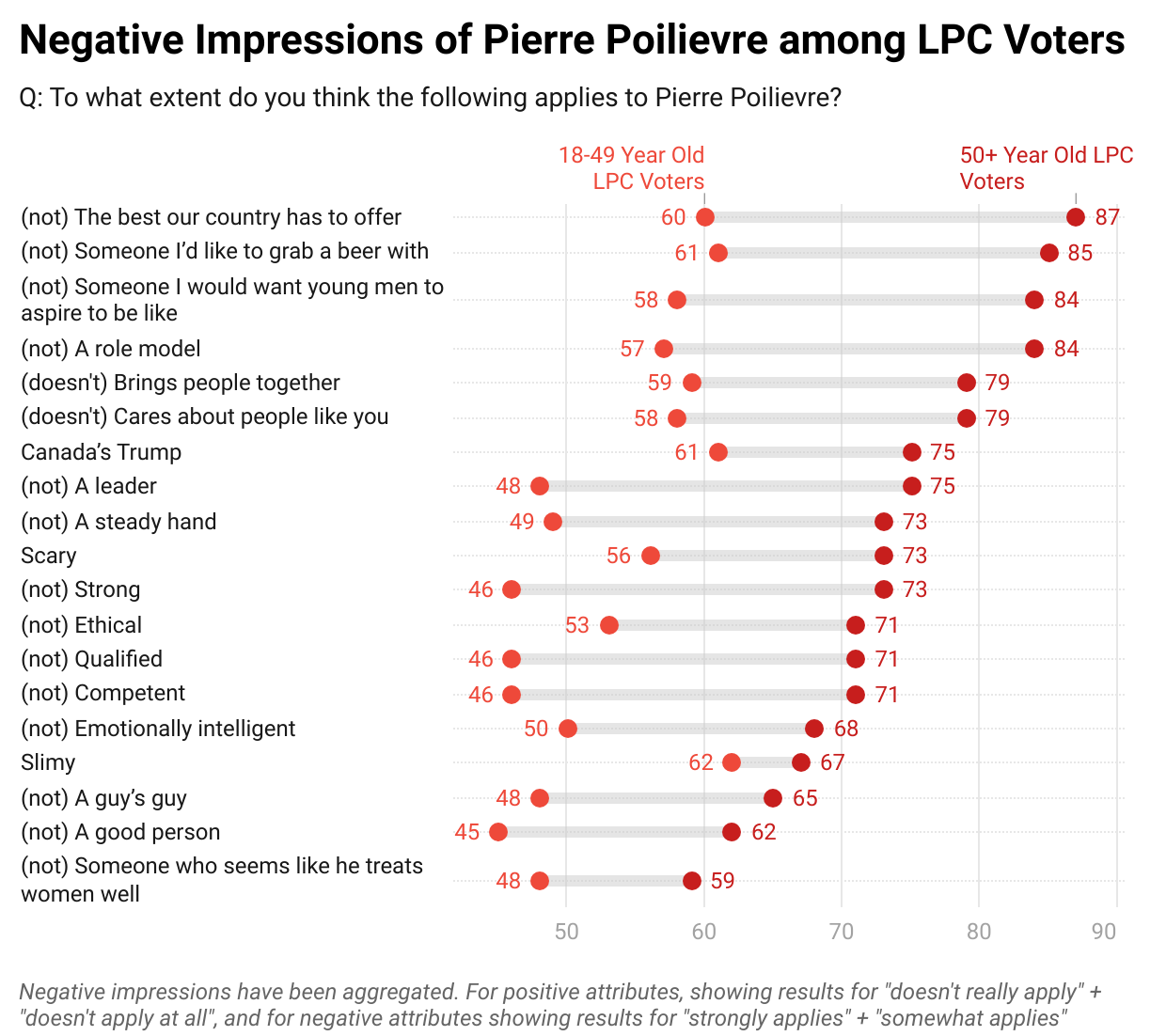

The centrality of the Canadian identity ballot question is apparent when looking at what Liberal voters, particularly older voters, think about Poilievre. To voters older than 50, Poilievre’s greatest flaws are basically that he’s not a good Canadian or a good person:

He’s not the best our country has to offer

They wouldn’t like to grab a beer with him (a true Canadian test)

They don’t want young men to aspire to be like him

They don’t think he’s a role model

They don’t think he’ll bring people together

They don’t think he cares about people like them

While 3 in 4 older Liberals think Poilievre is “Canada’s Trump,” this isn’t among their top-rated complaints. It’s a higher-ranked factor among younger Liberals, who tended to find Poilievre to lack the above qualities and to also be “slimy”. However, their opinions of Poilievre are a bit milder overall.

This assessment of Poilievre as un-Canadian is a conclusion I heard voters make organically. It wasn’t cultivated through Liberal content or ads. In qualitative testing, it sounded like “that’s just not very Canadian,” or “Canadians are meant to work together,” in response to Poilievre’s content or attack ads.

However, the centrality of Canadian identity as a campaign frame was very much reinforced creatively in the LPC campaign, such as through the “Good Neighbours” video about Gander on 911 or the “Elbows Up” ad with Mike Myers.

Politically, the big challenge for the Liberals in the coming months will be maintaining their new voter coalition. Given that this is a fourth Liberal term, I don’t think the party can take any voters for granted. However, voters, particularly older and less fickle voters, also formed strong views of Pierre Poilievre throughout the campaign. Given the extremely emotional basis for evaluating Poilievre, I don’t think opinions of him will be easy to reshape.

The Conservatives and identity politics

This next part isn’t really pertinent to the ballot question issue, but I’m going to shoehorn this conversation while we’re on the topic of identity. We know that when the Conservatives vanquished Justin Trudeau, they also got rid of identity politics. Or did they? Google tells me identity politics is “politics based on a particular identity, such as ethnicity, race, nationality, religion, denomination, gender, sexual orientation, social background, political affiliation, caste, age, education, disability, opinion, intelligence, and social class.” Well, if that’s the case, I’d argue that the Conservative campaign was as heavily fueled by identity politics as any of Trudeau’s, it’s just not how we typically think of it.

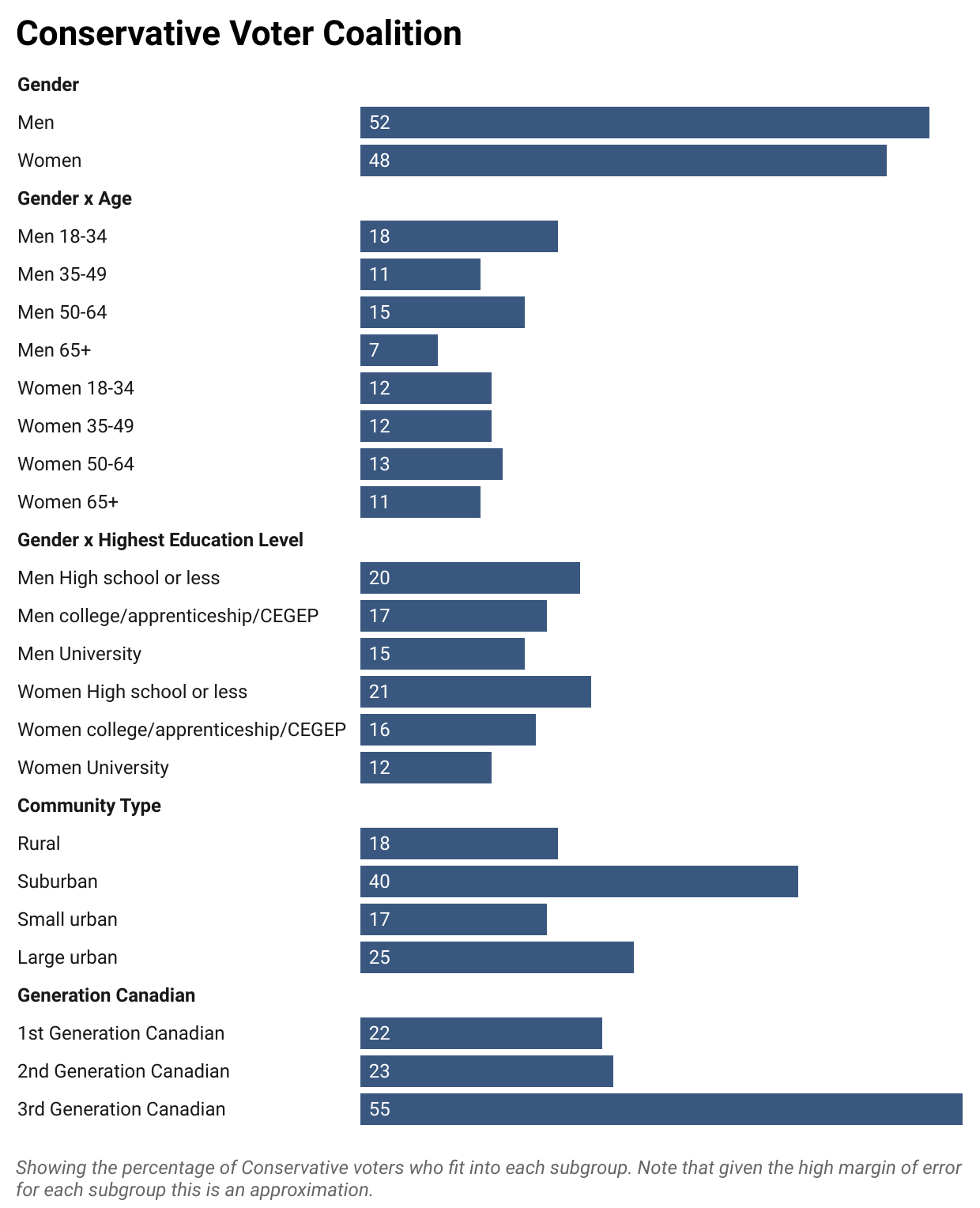

Let me first point out that the Conservative voter coalition is extremely diverse. While it skews more male (particularly younger men) than the general population, approximately 48% of their voters are women. And while they have more appeal among university-educated men than university-educated women, my polling doesn’t show a gap between non-university-educated women and men. Conservatives also performed well among both 1st and 2nd Generation Canadians, as evidenced by their strong showing in the 905 suburbs. Given the relatively small sample sizes of these groups, I’ll caution that the overall trend is important, not the precise figures. My point is that their vote was diverse.

Despite this diverse voter base, they aggressively pursued a specific type of voter: the boots, not suits crew. Or in their depiction, young blue-collar men. Beyond the slogan, appeals to this group of men were pervasive in their campaign imagery. Women were only mentioned 4 times in their platform. I’ll probably do a more detailed analysis of campaign ads another day, but if you look through their Meta ads, you’ll see all sorts of interesting ads directed exclusively towards men, like calls to “Free the Zyn”.

A fair rebuttal would be: well, it’s not identity politics. It’s just campaigning. And I would rebut your rebuttal by asking, where is the line between what is “identity politics” and what is simply marketing? It seems to me that it’s dependent on who the outreach is to.

Identity politics = Targeted marketing that isn't targeting me.